Manoomin, referred to as wild rice in English, is a sacred food and traditional dietary staple to the Anishinaabe nations Indigenous to the Great Lakes. The loose translation is “the good berry”. In our prophetic teachings, Manoomin is understood as “the food that grows on the water,” and her former widespread presence is how we knew to care for these places as our homelands.

Western science, which in recent years has begun to recognize the validity and veracity of Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge across a wide range of environmental focal points, has come to regard Manoomin as an “indicator species.” In essence, Manoomin requires healthy water, stable water levels, lack of invasive competitors, and a predictable temperature range. Further, this amazing grain feeds waterfowl and fishes, and is in relationship to a diversity of microorganisms and macroinvertebrates who compose the largely unseen web of life beneath the water and within the soil.

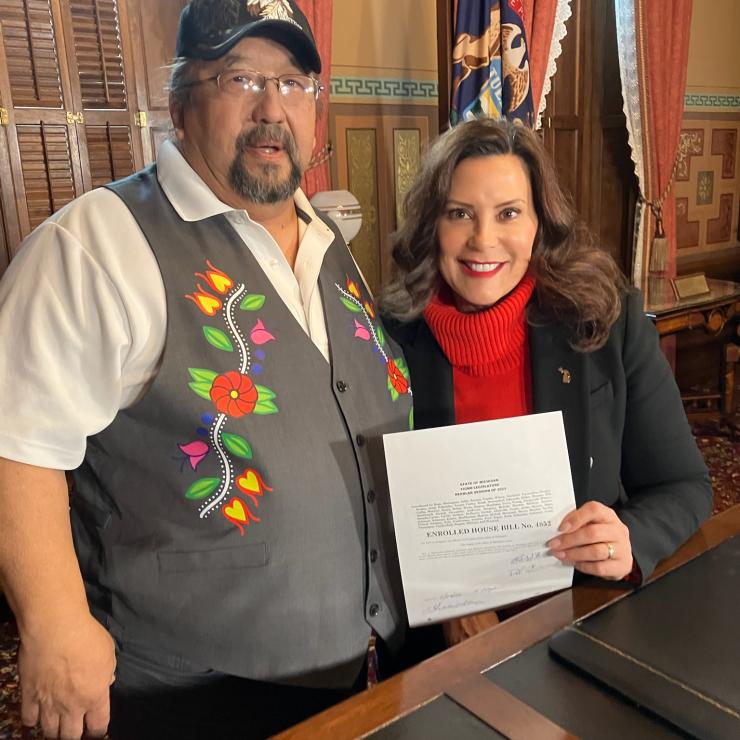

This November the Michigan legislature, with large bipartisan majority support in both the House and Senate, approved a bill recognizing Manoomin as Michigan's Native Grain. This legislation was quickly signed into law by Governor Whitmer.

Due to logging and agribusiness and chemicals and developments and dams and purposeful eradication based on ignorant labeling of this sacred plant as a weedy nuisance as well as to undermine and disrupt Indigenous lifeways, the formerly resplendent and vast Manoomin beds throughout the state of Michigan were nearly all destroyed. Due to the deeply entrenched influence monied special interests have on the priorities informing the decision-making of governing authorities, we are collectively baked into the fossil fuel dependency that is threatening the entirety of the living earth. The same teachings that instructed the Anishinaabe people to live alongside Manoomin also make it very clear that a time would come when humanity will have to choose between a road of continued destruction or a path of restoration. It has become apparent that for our current generation, that time is now and compromise is an illusion. Water is the first medicine, and necessary to life and healing, and yet is continually squandered for the sake of the profiteers in poison. The ramifications touch every facet of our collective security, as the proverbial ripple in the pond, for good or for ill.

My role as Mid-Michigan Organizer with Clean Water Action focuses on shutting down Line 5, the 70-year-old Canadian oil pipeline that poses such a terrible risk to the Great Lakes and all the bodies of water it crosses throughout its 645 mile course. Though 4 miles that run underwater at the Straits of Mackinac are a particularly absurd and obvious threat, the entirety of the infrastructure endangers the interconnected waters, flora and fauna of the basin overall.

On December 1st, the Michigan Public Service Commission (MPSC) approved the permit to construct a Line 5 tunnel. This irresponsible decision brushed aside not only the clear will of sovereign tribal nations to remove Line 5 altogether, but also ran counter to over 23,000 public comments they received. And it certainly was made without addressing the concerns of industry experts in engineering and geological surveying who have questioned the feasibility and safety of the proposed tunnel.

Both these recent developments - the recognition of Manoomin versus the coddling of the fossil fuel behemoth Enbridge corporation - are emblematic of two starkly divergent approaches to human interactions with the natural world.

Governor Whitmer revoked the easement that allowed Enbridge to operate on the bottomlands of the Straits back in 2020, and Attorney General Nessel continues as a steadfast protector of the Great Lakes. Though the oil continues to illegally flow, the Whitmer Administration’s determination to remove the threat of the Line 5 dual pipelines offers great reassurance that science and sanity can prove ascendant among elected officials.

On December 5th, in ceremonial acknowledgement of signing the Manoomin law, the Governor took a commemorative photograph with tribal elder Roger LaBine, honoring his long relationship with Manoomin as a culture carrier and protector. The large community of people connected to the preservation and reintroduction of Manoomin esteem Roger as the foremost expert and guardian of the food that grows on the water.

Roger LaBine and Governor Gretchen Whitmer at Manoomin bill signing

At a community potluck near Lansing that afternoon, he shared his story with some of these old friends and those of us who hadn’t yet met him in person but nevertheless directly benefited from his living legacy. An enrolled member of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Roger recollected first attending a rice camp with his uncle in 1972, realizing from that time how Manoomin gave him an identity as an Anishinaabe. In the 80s he realized that Manoomin’s absence from all other communities needed to be remedied, so the Anishinaabe people could again experience this necessary spirit relationship. The severance precipitated by the abuse of the waters was compounded by assimilation policies like relocation and the boarding school system - so to restore Manoomin is akin to restoring meaning and purpose to the people. In the early 2000s, he first began to advocate for a State government policy that would prioritize the restoration of water and habitat required by Manoomin.

Having achieved a measure of success stewarding the rice beds, Roger began to experience pushback against tribal restoration efforts by those who had normalized the mistreatment of water for the sake of convenience, or misinformed aesthetics, or perhaps just as a reaction against being regulated for the sake of culture and environment. He remarked that for him, the long journey to this point of Michigan state recognition comes with great emotion. There is now a chance for everything to align and assure great care be taken with education about Manoomin, so efforts to restore and preserve her occur in a respectful and sustainable way that aligns with 7th Generation teachings.

There is a sense of dissonance, between witnessing the MPSC’s shameful Line 5 tunnel decision, and a few days later celebrating this happy moment in a long saga of cultural loss and restoration. Within that context of emotional upheaval, I definitely took special notice of Roger’s repeated musing:

“I believe Manoomin must have been sent to me by Creator to teach me patience and perseverance.”

All of us who revere significant and sacred cultural touchstones like Manoomin become responsible for carrying that life and spirit forward, in gratitude and with determination. To despair, or fail to meet this responsibility, is to concede defeat. This would let down our ancestors, all who are yet to be born, and all those now living, including the other-than-human relatives who depend on good water just like we do. These truths are mirrored by the strength of the Water Protector movement, and provide hope that shutting down Line 5 is going to be the inevitable result of perseverance, truth-telling, and devotion to all our relations for the next 7 Generations.

Roger concluded by reminding us that the lighting of the 8th Fire is at hand. In that teaching, the Indigenous people and all other nations - including the progeny of the light-skinned races that previously made the ill choice to exploit and abuse - may yet decide to travel the path of life and recovery. The collective lighting of the 8th Fire will require prioritizing the water and the healing of the natural world. This is the importance and the power of our alliances.

Roger LaBine and Dr Nichole Keway Biber